Module 7: American Legal Realism | Jurisprudence I

The module covers critiquing formalism, challenging neutrality, judicial discretion, Holmes's "The Path of the Law", Critique of Formalism, ALR and the Courts and Misunderstandings about ALR.

Exploring Themes of American Legal Realism

The chapter on American Legal Realism discusses several key themes that illuminate the movement's core arguments and its lasting impact on legal thought. Here's a breakdown of these themes:

1. Critiquing Formalism and Mechanical Jurisprudence:

The chapter emphasizes how American Legal Realism emerged as a reaction against the dominant legal formalism of the time. **** Formalism, as described in the chapter, viewed law as a self-contained system of rules and concepts from which legal outcomes could be derived through purely logical deduction.

Realists criticized this approach as being overly abstract and detached from the realities of how law operates in practice. They argued against the idea of "mechanical jurisprudence," where judicial decisions were seen as automatic outputs of applying pre-existing rules to specific facts, without consideration of real-world consequences or social contexts.

The chapter highlights the Sugar Trust Case as an example of formalist reasoning leading to potentially absurd results. In that case, the court's rigid focus on legal categories, rather than the practical impact of a sugar monopoly on interstate commerce, led to a decision that seemed to contradict common sense.

2. Challenging the Neutrality and Objectivity of Legal Concepts:

Realists rejected the notion that legal concepts and standards are inherently neutral or objective. They argued that terms like "contract," "property," or "proximate cause" are not self-defining and often hide implicit policy choices and societal biases.

The chapter uses Judge Andrews' dissenting opinion in the Palsgraf v Long Island Railroad case to illustrate this point. Andrews argues that the concept of "proximate cause" in tort law is not a matter of pure logic but rather reflects societal judgments about where to draw lines of liability based on "convenience, public policy, [and] a rough sense of justice."

3. Emphasizing the Indeterminacy of Legal Reasoning:

Another central theme is the realist argument that legal rules and concepts are often indeterminate, meaning they don't lead to clear and predictable outcomes in all cases. **** This indeterminacy stems from the inherent ambiguity of language and the fact that legal principles are often formulated at a level of generality that requires interpretation in specific contexts.

This point echoes Holmes's famous statement that "General propositions do not decide concrete cases." The chapter explains that while specific legal rules might determine outcomes in straightforward cases, there is often a "logical gap" between general legal principles and the resolution of complex disputes.

This indeterminacy, according to realists, means that judges have more discretion than acknowledged by formalists. It also underscores the importance of considering social and policy factors in judicial decision-making, as these factors often fill the gaps left by indeterminate legal rules.

4. Unveiling the Role of Judicial Discretion and the Importance of Facts:

The chapter explores how realists sought to demystify judicial decision-making by highlighting the role of discretion. They argued that judges don't simply "discover" the law but actively make choices, influenced by their personal values, social context, and understanding of the facts.

Several realists, particularly Jerome Frank, stressed the significance of fact-finding in shaping judicial outcomes. They argued that the way facts are presented, perceived, and interpreted can greatly influence a judge's decision, even when legal rules appear clear.

The chapter illustrates this theme through provocative titles of realist writings like "Are Judges Human?" and "The Judgment Intuitive: The Function of the 'Hunch' in Judicial Decision". These titles suggest that realists wanted to expose the human element in judging and move away from the image of judges as purely objective and impartial decision-makers.

5. Advocating for a Focus on Social Science and Public Policy:

Given the indeterminacy of legal rules and the influence of social factors on judging, many realists advocated for incorporating social scientific insights into legal analysis and decision-making. They believed that a better understanding of human behavior, social structures, and economic realities could lead to more just and effective legal solutions.

The chapter highlights the "Brandeis Brief" as an influential example of this approach. In this brief, sociological and economic data about working conditions were used to argue for the constitutionality of a law limiting women's working hours. This marked a shift away from purely legalistic arguments towards a more pragmatic and data-driven approach.

6. Shifting the Focus to a Predictive and Pragmatic Understanding of Law:

Instead of viewing law as a system of abstract principles, realists encouraged a more pragmatic understanding of law as a tool for predicting what courts will actually do. This shift was meant to demystify law and encourage a more realistic view of its operation in society.

The chapter discusses the idea of looking at law from the "bad man's perspective," as articulated by Holmes. This perspective emphasizes that, for many individuals, law is primarily about understanding the potential consequences of their actions and predicting how legal authorities will respond.

7. Acknowledging the Influence of Social Context and Bias:

Building upon the previous points, the chapter implicitly acknowledges the potential for bias in legal systems. By emphasizing the role of social context, personal values, and power dynamics in shaping legal outcomes, realists opened the door for later critical legal movements to examine how law can perpetuate and reinforce social inequalities. This connection is subtle but significant, as it lays the groundwork for future critiques of law's role in issues of race, gender, and class. </aside>

<aside> 📌

Unmasking the Law: Themes in Holmes's "The Path of the Law"

Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr.'s seminal work, "The Path of the Law," offers a penetrating analysis of the nature of law and legal reasoning, anticipating key tenets of American Legal Realism. The following themes emerge from his insightful exploration:

1. Law as Prediction:

Holmes contends that the essence of law lies in predicting the actions of courts. He famously states, "The prophecies of what the courts will do in fact, and nothing more pretentious, are what I mean by the law." This pragmatic perspective shifts the focus away from abstract legal principles and towards the practical outcomes of legal disputes.

He encourages lawyers to view the law as a "bad man" would, concerned primarily with the material consequences of their actions and seeking to avoid legal repercussions. This perspective underscores the idea that, for many individuals, law is a tool for navigating potential risks and understanding the boundaries of permissible conduct.

2. Demystifying Legal Concepts:

Holmes challenges the traditional view of legal concepts like "rights," "duties," "malice," and "intent" as inherently moral or objective. He argues that these terms are often infused with moral connotations that obscure their true legal meaning, leading to flawed reasoning and misguided judgments.

He illustrates this point by examining the concept of "malice" in tort law. While it once implied a malevolent motive, Holmes argues that in a legal context, it simply signifies that an action was likely to cause harm, regardless of the actor's intentions. This example highlights how legal concepts can evolve over time and deviate from their original moral underpinnings.

3. Exposing the Limits of Logic:

Holmes criticizes the "fallacy of logical form" in legal reasoning. He argues that law is not a purely logical system deducible from fixed axioms. Instead, it is influenced by a complex interplay of social forces, historical context, and judicial discretion.

While logic plays a role in legal analysis, Holmes contends that it cannot fully explain the development of legal rules or predict judicial outcomes. He emphasizes the importance of considering "considerations of social advantage" and the "habit of the public mind" in shaping legal doctrine.

4. The Role of History and Tradition:

Holmes acknowledges the significance of history in understanding the law. He argues that legal rules often inherit their form from past practices and beliefs, even when the original rationale for those rules has faded. This historical baggage can lead to legal doctrines that are outdated, inefficient, or even contradictory.

He illustrates this point with the example of larceny and embezzlement. While both involve misappropriation of property, legal distinctions between these offenses, rooted in historical circumstances, can create loopholes and complicate prosecutions. This example underscores the need for critical re-evaluation of legal rules in light of their current social purpose.

5. Towards a More Rational and Purposeful Law:

Holmes advocates for a more conscious and deliberate approach to legal development. He argues that legal rules should be clearly articulated and justified based on their social purpose. He envisions a future where history plays a less dominant role in legal reasoning, and where economics and social sciences inform the creation and application of law.

He uses the example of statutes of limitation and prescription to illustrate this point. Instead of relying on vague justifications like the loss of evidence or the desire for peace, Holmes suggests considering the psychological impact of long-term possession on individuals, suggesting that a deep-seated human instinct to defend what we have long used can justify legal rules regarding possession. This example highlights the need to ground legal principles in a deeper understanding of human behavior and social dynamics.

6. The Importance of Jurisprudence:

Holmes emphasizes the importance of jurisprudence, the study of law in its most generalized form. He believes that a clear understanding of fundamental legal concepts is essential for effective legal practice and for developing a more rational and coherent legal system.

He criticizes the tendency to compartmentalize legal knowledge into specialized areas without considering the broader theoretical framework that connects them. He encourages lawyers to “look straight through all the dramatic incidents and to discern the true basis for prophecy," advocating for a more holistic and theoretically informed approach to legal analysis. </aside>

Legal Realism - Intro

The main goal: Realism aims to keep our thinking grounded in reality - things we can see, touch, or measure - rather than getting lost in idealistic or abstract thoughts.

Reduction: This is a key part of realism. It's about taking complicated or controversial ideas and trying to explain them using simpler, more scientifically-based concepts.

The process: When realists encounter a complex idea that isn't well-supported by science, they try to "translate" it. They attempt to express that idea using concepts that are more firmly rooted in scientific understanding.

Accordingly, the Legal realists' quest was to expel from the ‘science of law’ all but empirically verifiable propositions. Realists condemn as idealistic (unscientific) any categories of legal thought that cannot be reduced to empirical facts.

Obligation

So, for them the idea of an obligation is pretty much nonsense unless translated to the predictability of sanction (note the clear similarities with Bentham and Austin here).

<aside> 📌

Similarity with Austin

For Austin, an "obligation" exists because disobedience to the law will likely result in punishment—a predictable consequence.

Like Austin, realists view the idea of an “obligation” as meaningful only when it relates to the likelihood of a sanction. This means they agree with Austin’s focus on the practical, enforceable side of law, where rules are connected directly to consequences (like punishment or sanctions).

</aside>

Critique of "Idealism": Realists label as "idealistic" any legal ideas or principles that don’t have clear, empirical foundations.

<aside> 📌

For instance, an abstract principle like “justice” has no practical value unless it can be connected to real-world effects, such as predictable rulings in court or consistent enforcement practices.

</aside>

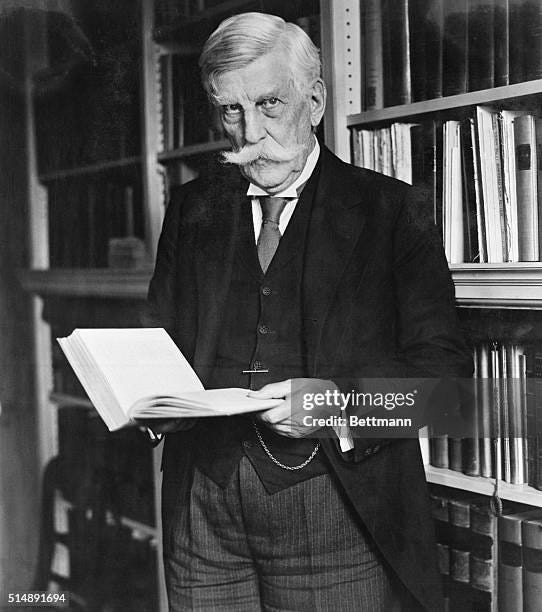

OLIVER WENDALL HOLMES JR

One of the most influential proponents of legal realism (specifically, ALR), Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., stated that

“The life of the law has not been logic: it has been experience.”

OWH argued that law is shaped more by practical experiences than by strict logic.

He believed that the rules that govern society come not just from logical reasoning, but also from factors like the needs of the time, popular moral and political ideas, public policy concerns, and even the personal biases of judges.

In other words, the way laws develop is heavily influenced by real-world conditions, rather than being a purely intellectual or abstract process.

We should cut through all the false moralistic language of the lawyers, judges, and legal commentators, by taking on the perspective of “the bad man”, who wants to know only what the courts are “likely to do in fact”.

Legal realists are inspired by the sociological jurisprudential view of Roscoe Pound, which assumed an instrumental view - there’s a difference between “**law in books” and “law in action”.

Colloquial Sense & Bad man

In "legal realism," the term "realism" is used in a colloquial sense—meaning a "realistic" or down-to-earth view. This isn't about philosophical realism but about being practical and worldly.

<aside> 📌

Legal realism calls for a clear-eyed, often skeptical view of how law works, focusing on what actually happens in the courts instead of idealized or theoretical interpretations.

</aside>

Bad man perspective Holmes famously illustrated this with his idea of seeing the law from the perspective of "the bad man." This "bad man" is the client who doesn’t care about the moral or philosophical arguments behind the law; he only wants to know what actions will lead to punishment and what won’t. This everyday or "colloquial" perspective on the law cuts through the formal, moralistic language often used by legal professionals and gets to the point: what outcomes are likely in practice.

‘Legal Obligation’ & ALR

The Realists thought the idea of a "legal obligation" wasn't very useful unless it could be tied to something concrete. For them, the only real meaning of "obligation" was the likelihood of facing a punishment or sanction for not following the law.

Holmes viewed legal obligations not as abstract moral duties, but as practical predictions of how the law would operate in real-world situations.

<aside> 📌

For instance, Holmes viewed a legal obligation—such as a contractual obligation—not as a moral promise to fulfill the contract, but as a prediction that if someone breached the contract, they would likely face legal consequences, like having to pay damages.

</aside>

In other words, the obligation was simply the likelihood of a penalty being imposed, not an inherent duty to perform the contract itself. Holmes’s perspective highlights the pragmatic and outcome-focused approach of ALR.

Focus of ALR

ALR primarily focused on judicial decision-making and challenged the traditional view of how judges arrived at their decisions. Here are the key points:

Fact-Centered Decisions and Biases: Legal realists believed that judges’ decisions were more often shaped by real-world facts and their personal or political biases, rather than by strict legal rules. These decisions could also stem from gut feelings or “hunches.”

Realists argued that instead of relying on abstract legal principles, judges were influenced by their perceptions of the facts, making the decision-making process subjective. Consequently, legal realists called for a greater role for public policy considerations and insights from the social sciences to guide judicial reasoning.

<aside> 📌

Adjudication is subjective.

OWH calls this: “think things, not words” - The examination of facts must dominate legal investigation. The object of a study of the law is ‘prediction’ – that is, ‘the prediction of the incidence of the public force through the instrumentality of courts’.

</aside>

Critique of Legal Reasoning: Legal realists criticized traditional legal reasoning, which presented itself as scientific and deductive, suggesting that legal rules and concepts were clear and neutral. However, realists argued that these rules were often indeterminate, meaning that legal texts and precedents did not always offer clear answers. As a result, legal decisions were rarely as neutral or objective as they seemed. This indeterminacy opened the door for judges’ personal inclinations to influence rulings.

<aside> 📌

Realists challenge the tranditional view of legal reasoning → legal rules were clear and neutral and decision making is scientific and deductive.

Realists → legal rules are often indeterminate and this opens the door for judge’s personal inclinations → decision making rarely objective or neutral.

</aside>

Indeterminacy and New Approaches: The uncertainty and flexibility of legal concepts meant that judicial decisions could not always be explained through legal reasoning alone.

Instead, other factors like hunches, biases, and the broader context needed to be considered.

Legal realists suggested that judicial reasoning should shift its focus to include social sciences and public policy, which would allow courts to address societal needs and realities more effectively.

ALR’s Critique of Legal Formalism

Formalism

Formalism is based on the idea that legal outcomes can be derived through a strict, logical application of rules.

Formalists believed that if you identified the right legal category or label for a case—such as “contract,” “property,” or “trespass”—the legal conclusion would naturally follow.

In other words, once the right legal principle was found, the judge would simply apply it to the facts, and the correct answer would emerge without ambiguity, like solving a math problem.

<aside> 📌

Example of Formalism

In the E.C. Knight case, the U.S. Supreme Court rejected the government’s attempt to regulate a monopoly in sugar manufacturing, even though the company controlled 98% of the nation’s sugar refining. The Court reasoned that manufacturing was distinct from commerce, and because the Constitution grants Congress the power to regulate interstate commerce (not manufacturing), it ruled that Congress had no authority to intervene.

The case was decided on labels; real-world consequences were treated as irrelevant to (or sub-versive of) the proper legal analysis.

This decision perfectly illustrates the formalist approach. The Court applied a strict, categorical interpretation of legal rules—separating “manufacturing” from “commerce”—without considering the broader real-world consequences of allowing a monopoly to dominate an essential industry.

</aside>

Challenge of ALR to Legal Formalism

ALRs challenged this view, arguing that legal decisions were not as automatic or predictable as formalists claimed.

They believed that judges often considered broader social, political, and personal factors. For realists, the law was more flexible and subject to interpretation, making judicial decisions less about finding the “right” legal label and more about balancing various competing interests and practical concerns.

The notion that most judicial decisions should or could be deduced from general concepts or general rules, with no attention to real-world conditions or consequences, critics labelled “mechanical jurisprudence”.

ALR and its attacks

The attack on formalist legal reasoning could be divided into two separate criticisms:

(1) arguing against the idea that common law concepts and standards were “neutral” or “objective”; and

(2) arguing against the idea that general legal concepts or general legal rules could determine the results in particular cases.

Attack 1: The Challenge to Neutrality and Objectivity

Realists argued that the common law concepts and standards, which formalists claimed were neutral and objective, were in fact laden with hidden moral and policy assumptions.

Legal categories and labels—such as “contract” or “property”—were not purely technical or value-free. Instead, they often masked deeper social and political judgments. Realists believed that these assumptions should be openly acknowledged and debated, rather than being presented as neutral or self-evident truths.

Example: Minority opinion in famous tort case: Palsgraf v. Long Island Railroad (1928)

In this case, a railroad employee negligently helped a passenger, causing the passenger to drop a package containing explosives, which led to an explosion that injured the plaintiff, who was standing some distance away. The central legal question was whether the railroad employee’s negligence “proximately caused” the plaintiff’s injury, meaning whether the injury was close enough in the chain of events to impose liability.

The majority opinion, written by Justice Benjamin Cardozo, applied a formalist approach, deciding that the railroad employee had no legal duty to the plaintiff, only to the passenger he was assisting. As a result, the plaintiff could not recover damages because the injury was too remote from the initial negligent act.

However, Judge William Andrews’ dissent in the case reflected a realist critique of the formalist concept of proximate cause. Andrews argued that proximate cause was not a logical, neutral principle but a reflection of practical considerations like public policy and justice.

As he put it: “What we do mean by the word ‘proximate’ is, that because of convenience, of public policy, of a rough sense of justice, the law arbitrarily declines to trace a series of events beyond a certain point. This is not logic. It is practical politics.”

Andrews’ dissent reveals the realist view that legal concepts were not scientifically precise or objective but were shaped by policy judgments and the practical needs of society. The realists, therefore, believed that law was a flexible tool for achieving societal goals, rather than a rigid system of rules and logic.

<aside> 📌

In proximate cause - you will draw a line which will determine the proximity - this line is based on the practical considerations - public policy and justice.

</aside>

Attack 2: Adjudication is not a mechanical application of general principles

Holmes famously encapsulated this criticism with the statement, “General propositions do not decide concrete cases.”

This highlights a fundamental flaw in the formalist approach: there often exists a logical gap between broad legal rules or statutes and the specific circumstances of a case.

In complex or difficult cases, simply applying general legal rules does not lead to a clear outcome. The application of these rules requires interpretation, which involves a degree of discretion and subjective judgment on the part of judges.

Later legal realists, such as Jerome Frank, took this critique even further. Frank argued that relying solely on legal phrases and concepts to reach decisions is misleading.

He claimed that such terminology does not provide a clear path to resolution; rather, it obscures the reality of decision-making in the legal system.

According to Frank, the conclusions reached in cases—like whether “proximate cause” exists—are often influenced by unstated assumptions regarding public policy or by underlying biases and prejudices that are not acknowledged in formal legal reasoning.

Attack 3: Law should be changed

Even when one can determine what the law is and it is sufficient to decide the case, it may be that the law should be changed.

While the realists weren't the first to question the morality of laws, their approach opened a new path for moral and practical critiques of established legal rules by challenging the view of law as a purely logical, closed system.

Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. voiced this realist attitude toward legal tradition in his famous statement:

“It is revolting to have no better reason for a rule of law than that so it was laid down in the time of Henry IV.”

Holmes pointed out that adhering to outdated laws simply because they have historical precedent is irrational if the reasons for those laws no longer apply.

Holmes, a strong proponent of judicial restraint, viewed his statement as support for legislative reform—meaning, he thought lawmakers, not judges, should be the ones updating or changing outdated laws.

However, other legal realists extended Holmes’s argument to suggest that judges themselves could reform or reinterpret outdated legal rules when necessary. This approach encouraged judges to see themselves not just as rule-appliers but as interpreters who could address evolving societal needs.

ALR AND THE COURTS

ALR and Decision-making

The traditional approach to judicial decision-making, has often been portrayed as a “syllogistic” method, where judges deduce rulings based solely on legal principles.

Legal realists criticized this view, arguing that judges often exercise discretion, making decisions based on broader factors rather than strict legal rules.

<aside> 📌

Example → Kesavananda Bharati v. State of Kerala (1973), exemplify this discretion. In this case, the court interpreted the “basic structure doctrine,” a principle not explicitly stated in the Constitution but inferred from broader constitutional values. This decision, far from being a simple application of legal rules, involved the court’s judgment about the essential features of India’s Constitution.

</aside>

Two Strands of Realist Thought on Judicial Decision-Making

Realists argue that judicial decision-making is:

Under-determined by Legal Rules and Precedent: Judges often face cases where legal rules could support multiple outcomes.

<aside> 📌

For instance, in Indian cases involving Article 21 of the Constitution (right to life and personal liberty), courts have made expansive interpretations that go beyond the literal meaning, recognizing rights to privacy, education, and even a clean environment.

</aside>

Highly Responsive to Facts: Judges’ decisions are strongly influenced by how facts are presented.

<aside> 📌

In Indian jurisprudence, this fact-sensitive approach can be seen in public interest litigation (PIL) cases, where courts have tailored their judgments to address specific social and economic issues, often stepping beyond strict legal boundaries to achieve justice for disadvantaged groups. The Bandhua Mukti Morcha v. Union of India case (1984) is a prominent example, where the Supreme Court considered extensive sociological data to address issues of bonded labor.

</aside>

Llewellyn’s Paper Rules vs. Real Rules

Karl Llewellyn, an influential legal realist, differentiated between “paper rules” (formal rules in legal texts) and “real rules” (the rules judges actually apply).

In practice, courts and judges do not always follow these black-letter rules rigidly. Instead, they often apply rules in a way that reflects practical needs, social norms, or unspoken assumptions that are not explicitly stated in the written laws.

Llewellyn referred to this pragmatic application as "real rules," which may differ from what is officially documented because judges tend to prioritize what works best in real-world contexts rather than adhering strictly to abstract, formal statements of the law.

<aside> 📌

In India, this distinction is apparent in the interpretation of commercial and contract law. For example, the Indian Contract Act’s section on “free consent” in contract formation is not applied in an abstract manner; courts often consider social and economic factors, such as unequal bargaining power or exploitative conditions, to determine whether consent was truly “free,” reflecting the realities of the Indian business environment.

</aside>

Llewellyn also emphasized that legal rules should align more closely with the social norms and expectations of its subjects.

He believed that, especially in areas like commercial law, where people engage in everyday transactions and contracts, laws should reflect how individuals in society genuinely interact and what they consider fair or binding.

<aside> 📌

For instance, if a community of business people considers certain practices binding in a transaction, then the law should reflect that norm rather than apply rules that may be overly formalistic or out of touch with business realities.

</aside>

2 themes in the writings of realists - general principles "do not" and “cannot” determine the results of particular cases

“Do not” claim: This claim is about how cases are actually decided in the real world. Legal realists argue that judges do not solely rely on general principles or rules to decide cases; instead, they are often influenced by extralegal factors like social context, public policy, and personal beliefs.

“Cannot” claim: This claim is about logical possibility, meaning that it is impossible to arrive at unique legal outcomes in every case using general principles alone. This view suggests that the nature of legal language and rules inherently lacks the precision needed to produce one determinate answer for complex cases. There is often a gap between broad principles and specific facts, meaning that deductive reasoning from general rules does not always yield a clear, objective result.

These two claims are independent. Realists used both claims to argue that law is not purely objective or determinative, embedding this dual view in modern legal education, where it is now widely accepted that legal arguments can reasonably be made for both sides of a complex case.

Solution to this gap - Social Sciences

This dual criticism supports the realist view that legal concepts lack complete neutrality and determinacy.

The realists turned to social sciences—such as sociology, psychology, and economics—to fill this conceptual gap.

By understanding human behaviour and the practical impact of legal rules, realists believed judges could make decisions better aligned with real-world needs and societal values.

<aside> 📌

An example is the Brandeis Brief in Muller v. Oregon (1908), which incorporated sociological data to support labor regulations. This approach demonstrated how factual research, rather than abstract legal principles alone, could influence judicial reasoning by providing concrete evidence of a law's social effects.

For example, in cases addressing environmental protection, Indian courts have utilized environmental studies and expert reports to craft judgments aimed at sustainable development, such as the M.C. Mehta v. Union of India cases, which involved issues like pollution control and industrial safety.

</aside>

Misunderstandings about ALR

The realists argued that we should view the law as it appears to "the bad man"—someone only interested in predicting what the courts will actually do, rather than in the law’s moral or theoretical justification. However, some later writers mistakenly took this view as a conceptual claim about the nature of law itself. This led to several critiques that missed the realists' actual intent.

As a conceptual claim, the prediction-based view of law has obvious limitations:

Judges on the Highest Court: If law were purely about predicting judicial behavior, then what guidance would this offer to judges on a nation’s highest court, as there is no higher court whose decisions they can predict? Since no court sits above it, its judges cannot base their understanding of law on predictions of other judicial decisions, as there are none left to consider.

Law as Guidance: Law isn’t just a product of judges’ actions but a guiding system of rules and standards. Judges are expected to interpret and apply these rules in good faith, not merely act as if they’re predicting their own behavior.

Judicial Identity: Legal rules define who is recognized as a judge. This conceptual framework supports the authority and legitimacy of the judicial system, beyond simply describing outcomes.

Realists’ True Intent

The realists’ “prediction theory” was NOT intended as a rigid conceptual claim. Instead, it aimed to challenge the overly abstract, rigid, and formalistic view of law that dominated legal thought at the time.

They wanted legal professionals to consider how law operates practically, at "ground level," for the ordinary citizen. For most citizens, the law is experienced as the likelihood of certain outcomes—what a judge will rule or how law enforcement will act—rather than as a philosophical or moral structure.